- Sunshine Time

- Posts

- Fast Cars, Short Shorts, and a Lie That Stuck

Fast Cars, Short Shorts, and a Lie That Stuck

I need to talk about the Confederate flag. And Bo and Luke Duke. And how a generation of us got told a lie dressed up in horsepower and denim short-shorts.

I grew up thinking that flag was just a symbol for rebels and rascals. You know - fast cars, dirt roads, and that good old-fashioned Southern mischief. The General Lee wasn't a threat; it was a punchline. A vibe. Like a sheriff's badge in a dress-up box - plastic, shiny, and dangerous in the wrong hands.

Bo and Luke Duke weren't racists. They were charming. Hot. Heroes. The kind of guys who slid across the hood of a car like it was a stage.

And right there on the roof of that car was a big, bright RED, WHITE, AND BLUE Confederate battle flag.

I didn’t know what it really meant. But it sure looked awesome. Badass. Bold. Striking.

Nobody told me that flag was carried by men who fought to keep slavery legal. That it was raised again a hundred years later to protest school integration. That it’s been waved by Klansmen, lynch mobs, and mass shooters.

Because on TV, it meant “freedom.” It meant “fun.” It meant “good ol’ boys, never meanin’ no harm.”

And that’s the lie.

The General Lee and the "Rebel" Myth

The Dukes of Hazzard, which aired from 1979 to 1985, presented itself as a lighthearted action-comedy set in rural Georgia. The show's creators and stars often defended the General Lee's Confederate flag, often referring to it as the "rebel flag," as a symbol of the Duke boys' defiance against corrupt local authority, embodied by Boss Hogg. In this narrative, the flag was framed as an emblem of "Southern pride" and an underdog spirit, aligning with a broader cultural shift in the late 1970s and early 80s that sought to reframe conservatism as a rebellious, anti-establishment movement.

For many viewers, particularly white audiences, this interpretation took hold. The flag became synonymous with the car chases, the charming characters, and the fun-loving antics, effectively disconnecting it from its true, painful history. The show, whether intentionally or not, contributed to a widespread ignorance, coating a symbol of hate in a veneer of charm and nostalgia.

So I got a story for ya - as one of those white viewers:

Once upon a time, I was a 13 or 14 year old runaway in the streets of Southern California. Lost, scrappy, trying to figure out who I had to be to survive. Somewhere, somehow, I found a Confederate flag bandana. And I wore that thing on my head like it meant something - like it made me tougher, louder, freer. A rebel.

Someone tried to call me out. And I argued. Not because I believed in white supremacy. Not explicitly, anyway. Not that I was aware of. That realization would come much, much later.

But because I was clueless. I had no idea.

It’s embarrassing now, yeah. But it was real. I thought I was making a statement. I didn’t realize it was one soaked in blood and hate.

That’s what media like The Dukes of Hazzard did to us. It didn’t teach us hate; it taught us ignorance. It coated everything in charm and car chases until we couldn’t see what was right in front of us.

Nobody warned us. Not the networks. Not the schools. Not even the people who loved us. Come to think of it, given my conservative upbringing, especially not them.

Was it intentional? Sometimes.

Was it racist? Always.

Even when it was smiling and cute and funny and sexy.

That flag on the General Lee helped clean up a symbol of hate and feed it to us as nostalgia. And millions of white kids like me learned to love it without ever knowing why.

But now I know better.

I now know that sporting that bandana was a bad fucking idea, and racist as shit.

But I’m not wearing that particular lie anymore.

If this truth stings and itches, let it.

That’s how healing starts.

That's more than just a metaphor; well, it is a metaphor, but it's a very personal one. One that I mean in my flesh. In my skin.

See, I live with dermatillomania. It's a body-focused repetitive behavior, in the OCD family of disorders. When things feel too big or too loud inside me - when I’m ashamed or anxious or overstimulated - my body tries to take control the only way it knows how.

My hands start searching for something on my skin. A bump. A scab. A tiny imperfection I can fix. Smooth out. Erase. Make perfect. A stress reaction.

It feels like I’m calming myself, but most of the time, I’m just causing new damage. Skin that wasn’t hurting starts to hurt. And it’s all because I couldn’t sit still with the feeling. With the itch. The discomfort.

That’s what I mean. That’s what some truths are like.

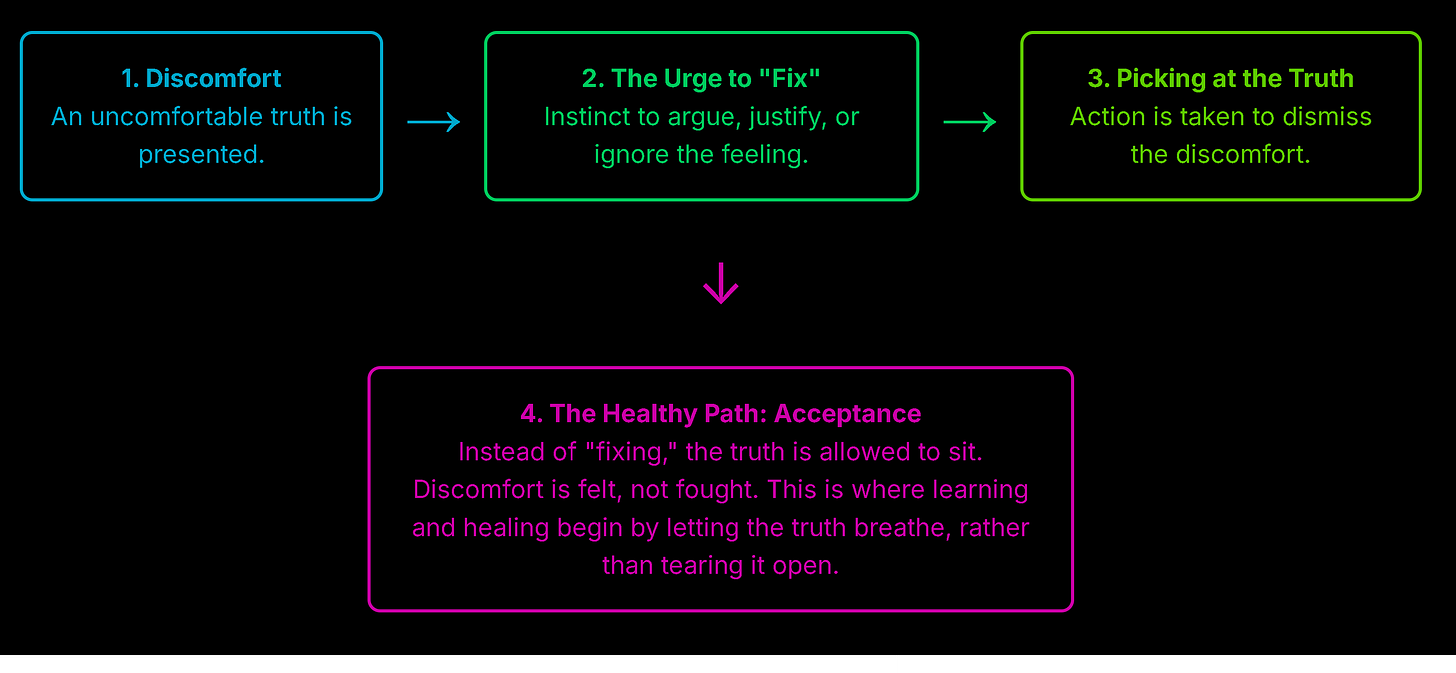

Not a scream. Not a slap. Just… a low hum under the surface. A discomfort you don’t know how to name. And the urge is to do something - to pick at it. To justify it, argue with it, explain it away.

But truth isn’t asking for a defense. It’s asking to be left alone long enough to settle. To be felt, not fought.

Like skin, truth doesn’t always heal when you mess with it. It heals when you stop interrupting it. When you let it breathe.

So yeah - when I say "let it sting, let it itch"; let it sit. Let it stay long enough that it teaches you something.

Not every discomfort is a flaw. Not every pain is a problem to solve. Some things, like healing, only happen when you stop trying to tear them open. I pick at my skin the same way I clung to that bandana - trying to fix something, trying to feel safe. But some lies don’t smooth out. They fester, unless you let them go. Truth too, as well as time, can heal some wounds.

What lie did you fall in love with?

What costume did you wear before you knew what it meant?

When did it finally start to itch?